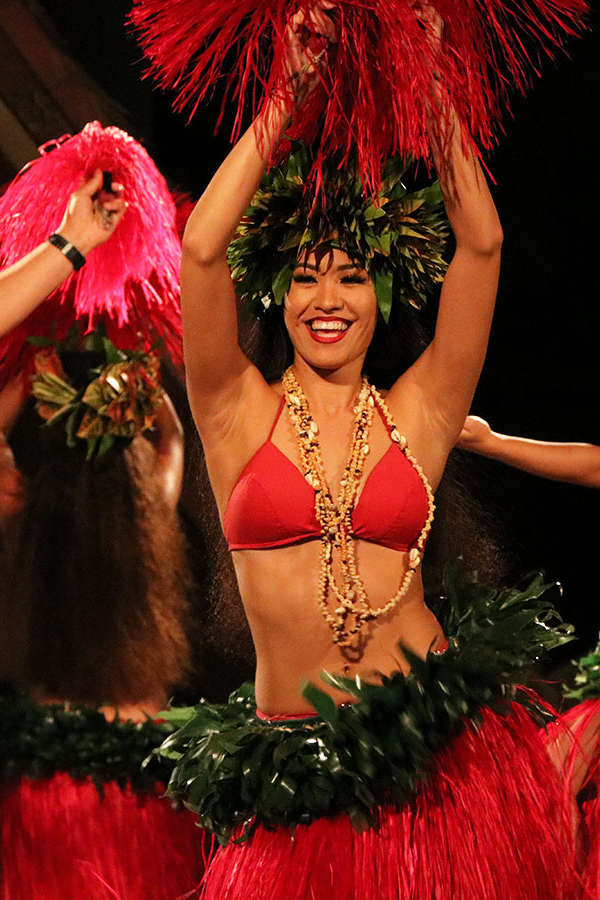

Picture a warm Hawaiian evening: guests gather beside a crackling imu (underground oven), fragrant steam rising from kalua pig, ukulele music drifting on tropical breezes, and dancers swaying in vibrant hula. In this article, we’ll explore Hawaiian luau history, uncover the traditional luau meaning, and examine the luau cultural significance. You’ll also discover how to honor this legacy through proper etiquette.

Hawaiian Luau History

From ʻahaʻaina to “luau”

Ancient Hawaiian celebrations were known as ʻahaʻaina, meaning “gathering meal”—formal events centered around cultural rituals rather than entertainment. Diverse rituals commemorated births, harvests, canoe landings, and victories.

The Kapu System & Its Breakdown

Under the strict kapu spiritual system, rules determined food access and seating: men and women ate separately, and certain foods like pork and bananas were reserved for chiefs. Then in 1819, King Kamehameha II officially abolished these taboos in a movement known as ʻAi Noa (“free eating”), prompted in part by high priest Hewahewa and royal advisers. This moment—when men and women first ate together in public—gave rise to what we now call the luau.

Evolving Terminology & Celebration

By 1856, the term luau (an iconic dish of young taro leaves in coconut milk) had overtaken ʻahaʻaina in everyday usage. Over time, the luau shifted from a chiefly rite to a broader communal festivity, eventually adapting into tourist-friendly dinners with hula kahiko and fire‑knife dance shows.

Traditional Luau Meaning

More Than Just a Meal

Derived from the Hawaiian word for young taro leaves in coconut milk, the luau dish itself became the namesake of these feasts. These gatherings became a powerful symbol of unity, familial bonds, and reciprocity.

Symbolism of Traditional Foods

- Poi (taro paste): A staple symbol of ancestry and life; eating from the same poi bowl fosters unity and peace.

- Kalua pig: Cooked in an imu underground oven, it represents the bounty of the land and the communal spirit of the feast.

- Laulau, lomi-salmon, poke, haupia: These dishes reflect land and sea gifts, and reinforce social connections and gratitude.

Ceremony & Respect

Originally, kapu rules governed seating and who could eat which foods. While modern luaus are more inclusive, vestiges of respect remain—leis presented with both hands, mindful listening during pahu drum cues and honoring altar-centered rituals.

Luau Cultural Significance

Reinforcing Hawaiian Identity

Luaus reinforce ʻohana (family), ʻāina (land), and ancestral memory. They became central to the Native Hawaiian cultural renaissance of the 1970s–80s.

A Platform for Cultural Exchange

These events act as cultural ambassadors: through food, chants (mele), hula, and shared narrative, they educate visitors about Hawaiian history, respect, and worldview.

Spiritual, Social & Educational Roles

Traditional music and dance—notably hula kahiko—tell stories of gods and ancestors. The imu ceremony and group feast encourage intergeneration transmission of knowledge and values.

Tips for Respectful Participation

- Arrive early – often 30–60 minutes before dinner starts to view imu rituals.

- Dress appropriately – aloha wear or casual resort attire; cover shoulders if entering any sacred space.

- Photography etiquette – wait for designated photo moments, especially during the ceremony.

- Accept leis & blessings graciously – “Mahalo” with both hands.Honor the performance – remain seated and attentive during chants and hula.

- Engage genuinely – ask questions; listen to host stories; and partake in community energy with humility.

Feast. Dance. Connect.

From ancient ʻahaʻaina to modern adaptations, this celebration remains central to Hawaiian identity. Whether you’re savoring tender kalua pigs or moving with hula, every element invites you into a deeper connection with the islands and their people. To experience this significance firsthand, consider booking an authentic luau with HawaiiActivities.com.